Originally posted at Markets for Good

It is becoming an article of faith that more data helps people make better decisions. But not all data is created equal. To be meaningful, data needs to be seen in context. This is particularly true of data about the performance of nonprofits or other social enterprises. Funders and government agencies routinely compel social programs to track and report financial and social outcomes but, too often, are not in a strong position to know what to make of the resulting numbers.

One way to give performance data context, and ultimately meaning, is through peer benchmarking. A growing number of experiments are aggregating data across networks of similar social programs or enterprises to construct peer benchmarks.

One example of this emerging strategy is Capital Impact Partner’s HomeKeeper project. HomeKeeper is a Salesforce.com application that helps nonprofits manage affordable homeownership programs. Capital Impact aggregates data from the 60 organizations using the system and automatically generates social impact reports that help each of the participating programs better understand their social performance.

By enabling programs to see how their performance compares to a national peer group, HomeKeeper makes the data far more salient and actionable.

For example, most affordable housing programs seek to ensure that families spend no more than one-third of their income for their housing costs. But most programs make exceptions to this rule for a number of circumstances such as when a family has been successfully paying more and their cost burden will be decreased in their new home. These kinds of exceptions are necessary and appropriate but one of the first pilot HomeKeeper users was concerned to find that nearly 20% of their buyers were paying more than 33% of their income.

Without context it is hard to know whether this 20% represents a serious problem or not. It was tempting to jump to the conclusion that this program was failing to ensure that the buyers of their ‘affordable’ housing could actually afford their new homes. But, it turned out that across thousands of transactions in dozens of programs, about 27% of buyers were paying more than the 33% standard. As housing costs have risen, lower-income families in high cost markets have become accustomed to paying what was historically a high share of their income for housing – the exception had become more of the rule.

And it turns out that these programs have been successful in serving these buyers with few or no loan defaults which suggests that a program with 20% cost burdened buyers may not have much cause for concern. Without the context provided by peer benchmarking, we could well have drawn the opposite conclusion.

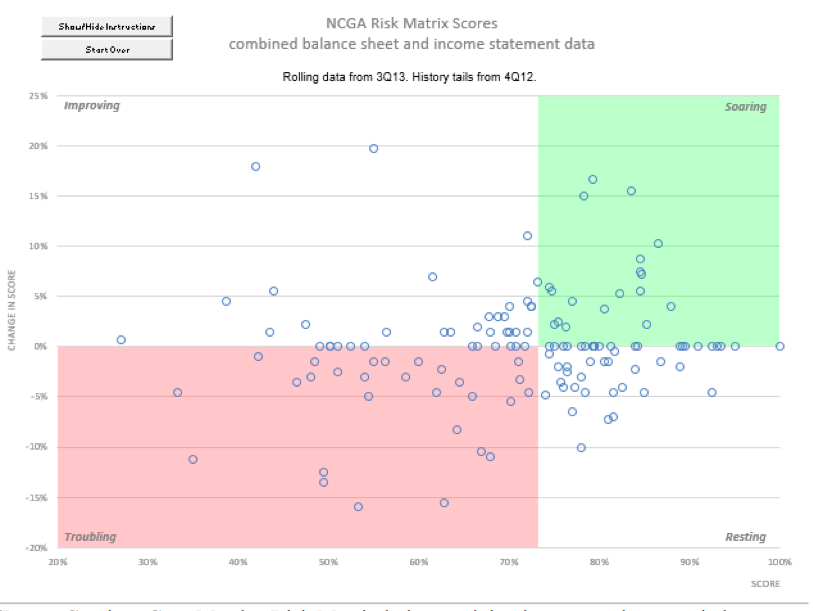

We see this same dynamic at work with CoopMetrics, which is focused on peer benchmarking of financial data for social enterprises.

CoopMetrics pulls data from accounting systems and automates the process of mapping very different financial statements to a common chart of accounts so that participating organizations can see their financial performance in context of their peer group. Again peer benchmarking makes better decisions possible.

For example, at one point, CoopMetrics founder, Walden Swanson, was conducting a data dive with a peer group of produce managers from dozens of natural foods cooperatives from across the Northeast. To Swanson’s surprise, a general manager of one of the stores walked into the meeting.

The GM pulled Swanson aside to let him know why he was there. His store’s produce department margins had been declining. He wanted to fire his produce manager, and he was there to find and recruit the best performing produce manager in the region.

As the GM watched from the back of the room, it did not take long to discover that everyone’s produce department performance was down. The group grappled with the reasons why and concluded that there was a common cause; it was an El Niño weather year and rising produce prices had pushed everyone’s margins down.

The store whose GM wanted to get rid of his produce manager was actually performing in the top quartile. As it turns out, he already had one of the highest performers! The problem was that without this kind of comparative benchmarking, it is impossible to really understand what is driving your overall performance.

We expect the ecosystem for data tools that advance decision-making in the social sector to begin to evolve at a more rapid clip. Collaborative data approaches that enable peer benchmarking are an essential component to the data ecosystem.